On December 30, 1937, Frank Lloyd Wright sent a telegram home to Wisconsin from Phoenix. It had been a hectic time for the architect: He’d spent months negotiating a contract to design the headquarters of Johnson Wax in Racine, Wisconsin, about 140 miles from hisTaliesin compound. It was a much needed big commission during the Great Depression, when he struggled to land clients and watched many of his most ambitious plans vaporize for lack of funding. Wright was seventy and under orders to relax—doctors told him and his third wife, Olgivanna, that winters in Arizona would help him recover from a bout of pneumonia the previous year. But he was restless in the desert, eager to make something new.

The telegram’s recipient in Spring Green, Wright’s assistant Gene Masselink, was well aware of Wright’s affection for Arizona. Members of the Taliesin Fellowship, Wright’s band of architectural apprentices, had spent multiple winters during the past decade piling into cars for the long drive from Wisconsin, staying in cheap hotels or quickly assembled camps outside Phoenix. Now, though, Wright was determined to set up a permanent winter residence for his fellowship and family. By the end of 1937, confident that a deal with Johnson Wax would provide steady infusions of cash, Wright finally had the resources to purchase a site in Arizona and start building.

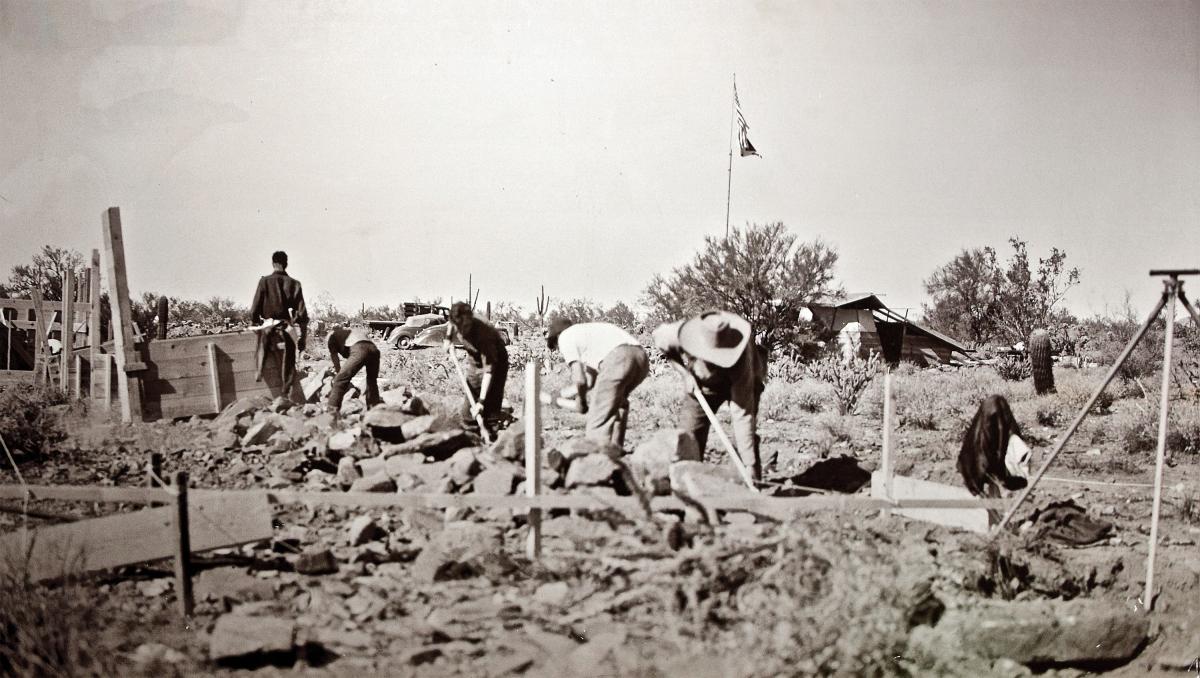

The telegram reads as if Wright couldn’t wait another minute to get going. He commanded Masselink and the rest of the cohort to all but clean out the Wisconsin compound and head west as soon as possible. Wright had architectural as well as cultural ideas to explore; they were going to build, and make art and music while they were at it. “Weather warm beautiful site in hand,” it reads. “Come Jokake [Inn, a hotel near Phoenix] soon you are ready bring shovels rakes hoes also hose. Eighteen drawing boards and tools. Wheelbarrow concrete mixer small Kohler [generator] and wire. Melodeon oil stoves for cooking and heating. Water heater viola cello rugs not in use and whatever else we need.”

Until then, the Arizona desert was pockmarked with sites for which Wright had grand ambitions that never left the drafting table. This time, with violas and rubble and cement mixers, he’d finally create something permanent.

Nineteen thirty-eight was Wright’s annus mirabilis. Time magazine put him on its cover. He’d completed his iconic Pennsylvania residence, Fallingwater. And he broke ground on Taliesin West—it, too, a masterpiece that exemplified his philosophy that a building should fit its environment like a nest in a tree. Planted at the foot of the McDowell Mountains east of Phoenix, 1,600 feet above sea level, Taliesin West was intended to “belong to the desert as though it had stood there during creation,” Wright wrote in his autobiography.

The place sneaks up on you; the low-slung buildings of the compound are all but invisible on the uphill drive there until you’re practically upon them. The rust-and-white color scheme of the exterior walls and beams echoes the surrounding landscape, and the “desert rubble stone” building technique Wright and his apprentices employed—nearby rocks and boulders placed into forms and then set in concrete—harmonizes with the angles and color palette of the mountain range it inhabits.

Yet Taliesin West also asserts itself. A triangular main courtyard thrusts forward from the facility like a ship’s prow, pointing southwest and facing what was then an unspoiled view of the Sonoran Desert. (Wright was crushed by the installation of power lines visible from there in the late ’40s, and unsuccessfully lobbied president Harry S. Truman to have them buried.) The seafaring metaphor extends further, because Wright imagined Taliesin West as a communal space, in which the 40 or so members of the Taliesin Fellowship were effectively deckhands, pressed to both work and play in close quarters. Wright and the fellows would meet with clients and design projects on-site, but Taliesin West was also meant to be a living space and a cultural hub as well: The fellowship were expected to sing, perform, cook, and socialize in addition to their daily labors. A wall of Taliesin West’s music pavilion bears a quote from the poet Lao Tzu that captures the sentiment: “The reality of the building does not consist in roof and walls but in the space within to be lived in,” it reads.

It’s a meaningful enough quote to Effi Casey, a former music director for the fellowship and artist who lives on-site, that she insists on making sure I see it, walking me across Taliesin West’s pergola, past its still-active studio filled with architecture students, to the pavilion. “[Taliesin West] was the adventure of coming out to a totally remote location,” she says. “We’ll entertain ourselves. We’ll share each other’s talents and music and singing and dancing and painting and sculpture.”

The need for the fellowship to entertain itself was acute because there wasn’t much else around. Phoenix was barely a city in 1940—its population was approximately 65,000—and the city center was 26 miles from the site. That distance helped Wright economize: He’d acquired the land cheaply (800 acres at $3.50 an acre), in part, because there was no evidence of groundwater on the site. (A well digger eventually had to drill 486 feet.) But Wright treasured remoteness. “Clients have asked me: ‘How far should we go out, Mr. Wright?’” he once wrote. “I say: ‘Just ten times as far as you think you ought to go.’”

The trade-off for that distance was that the fellowship, which formally launched in 1932 as a school (though also often criticized as a form of indentured servitude), needed to be a self-sufficient community. Members cooked and built together, and were expected to convene for Sunday evening formal dinners, write and perform music and skits, and attend movie screenings. All were expected to engage in some kind of performing art, even if you had little musical interest or talent; choir practice, Casey recalls, was at 7:15 a.m. sharp.

“An awful time to be singing,” says Casey. “I’d think, ‘Now I have to get up there and be totally enthusiastic about it, wake everybody up.’ However, my husband [Tom, a fellowship architect] always said, ‘After singing for 45 minutes before you go and deal with clients or contractors, you really felt you had it together.’ You were refreshed.”

Wright’s thinking about architecture was closely linked to his affection for music, Casey says. (She counts as we walk; there are currently five pianos on site.) “Frank Lloyd Wright enjoyed Vivaldi a lot,” she says. “I think because Vivaldi was a master in texture and patterns. One instrument goes dah dah dah dah, another duh duh duh with a soft line underneath. It’s a very rich combination of patterns, and I think Frank Lloyd Wright very much related to that.”

Culture didn’t necessarily equate to order, however. Though the site looks tame and polished now, drawing approximately 100,000 visitors annually, it was constructed slowly. By 1940, its central sections—including the main drafting area, kitchen, and Wright’s office—were complete, but it wasn’t until the late ’50s, toward the end of Wright’s life, that the Music Pavilion bearing Lao Tzu’s quote was finished. Minerva Montooth, the wife of fellowship architect Charles Montooth, recalls visiting the site for the first time in 1947, struck by the ongoing lack of infra-structure. “It was rough in those days, really rough,” she says. “It had been here 10 years and they had not done anything. No glass, no plumbing. And the electricity was not working because Mr. Wright had not paid the bill.”

But Wright was familiar with that kind of chaos. Indeed, ten years earlier, about 30 miles away, he’d rehearsed for it.

Wright first came to Arizona in 1928 for two reasons: to test an idea and to escape his reputation.

The idea was connected to a project by a former apprentice, Albert Chase McArthur, who was the lead architect for the Arizona Biltmore Hotel, a resort abutting Camelback Mountain in Phoenix. The Biltmore was meant to be a playground for the nascent culture of wealthy tourists in the Southwest, and though it was officially McArthur’s commission, Wright’s input was substantial. He had been testing a “textile block” system for a handful of California residences that used affordable concrete blocks at the center of the structure’s design. The Biltmore was an opportunity to explore it at a broader scope, and the final product, which remains a tony resort today, is defined by its gray yet stylish textile blocks. But Wright, displeased with McArthur’s execution, never put his name on it.

As for his reputation, he’d been tabloid fodder for much of the 1920s. Wright was cohabiting with Olgivanna Hinzenberg, a Montenegro-born dancer and composer, while he was still married to his second wife, Miriam Noel. The relationship, especially the birth of Hinzenberg and Wright’s daughter, Iovanna, in 1925, stoked Noel’s fury and caught the attention of law enforcement: Wright and Olgivanna were arrested in 1926 under a loose interpretation of the Mann Act, which prohibited transporting a woman for purposes of prostitution. By 1927, the drama had mostly subsided: Wright divorced Noel and the Mann Act charges were dropped. The following year, Wright and Olgivanna married. Arizona provided a reprieve from reporters and moralizing lectures. “No longer ‘fugitive from justice,’ I gladly turned into quarters at Phoenix and worked some nine months during a characteristic Phoenix summer (118 degrees in the shade),” he wrote in his autobiography. “I was to remain behind . . . the scenes, glad to do so.”

While working on the Biltmore, Wright met Alexander J. Chandler, a former veterinarian who had developed a suburb bearing his name southeast of Phoenix. He owned the San Marcos hotel, a downtown Chandler resort, and commissioned Wright for a grander project, called San Marcos-in-the-Desert, that would provide a fuller implementation of the textile block system, with a triangular design scheme to evoke the zigzagging skyline of the nearby mountains. “This desert resort I meant to embody all worthwhile I had learned about a natural architecture,” Wright wrote. “The building was to grow up out of the desert by way of desert materials.”

To do that, he needed members of his fellowship near at hand. In early 1929, Wright and 15 apprentices headed to Arizona and established a work camp about 10 miles west of the San Marcos hotel. Alternately named Ocatilla or Ocatillo, after the spiny desert cactus, the camp was a set of low buildings constructed of wood, with canvas-covered windows and roofs. Low barriers were designed to keep out snakes and scorpions, but life in the camp was punishing all the same. In May 1929, Wright lamented in a letter to his friend Darwin D. Martin that the fellowship had “almost no physical comfort. . . . I do not know how much longer we can hold out.” In a handwritten addendum, he noted: “The rattlesnakes keep us watching our step now. We have had seven as guests, to date,—two we put into captivity. Scorpions, centipede, tarantula and various other damage dealing insects are appearing. You see we are in unbroken wilds—the flies are awful.”

For all its instability, Ocatilla proved a valuable experiment in natural architecture. The camp buildings had sloping, angular designs meant to suggest seaworthiness, its canvas coverings hung as if from masts. “When these white canvas wings, like sails, are spread, the buildings . . . will look like ‘desert ships’” and “the group . . . like some kind of desert fleet,” Wright wrote. And for all the rough living the fellowship endured during their five months here, Wright made sure a piano was on site.

Ocatilla wouldn’t last. The canvas coverings proved a poor barrier against the punishing heat. Part of the camp burned down in June, and the stock market crash that fall wrecked the plans for San Marcos-in-the-Desert, though Chandler wouldn’t officially pull the plug until 1931. By then, Ocatilla had been abandoned and dismantled by scavengers.

Still, the fellowship would return to the Phoenix area throughout the ’30s, often staying at one of Dr. Chandler’s hotels. (Today, statues of Wright and Chandler are placed steps from each other in downtown Chandler. Wright is stately and pensive, wearing his trademark cape; Chandler sits and looks up toward him, as if in admiration.) Commissions were hard to come by. Since arriving in Arizona in the late ’20s, he’d drafted seven projects in the Chandler area before starting Taliesin West; none were built. The fellowship, Wright wrote, was “very happy there . . . but crazy to build for ourselves.”

In time, Taliesin West became both a home and functioning permanent camp. Boulders that bore the artwork of Native American desert tribes were positioned around the site, reminders that Wright and his followers weren’t the mountain ridge’s first occupants. One of those petroglyphs, a “whirling arrow” that depicted a pair of spirals entwined in a kind of handshake, would become the facility’s symbol.

The site became the winter training ground for Wright’s apprentices, who were expected to build small residences for themselves onsite—a practice that continues to this day at the architecture school housed at Taliesin West. And, just like with everything else, the fellowship was expected to make performances a part of their routine. Montooth, who was married in Taliesin West’s cabaret in 1952, recalls a full-dress production of the Gilbert and Sullivan opera Patience as well as original dance performances choreographed by Olgivanna (now Lloyd Wright) and led by her daughter Iovanna, a professional dancer. It made for a bruising schedule. “Rehearsals for those early dance performances were till midnight after the work day, after the cooking and dishes and everything,” Montooth says.

The fellowship opened some of these performances for the public, but Montooth stiffens when asked if they were ever meant to serve as fund-raisers for the ever-cash-strapped Wright. “There was never such a thing as a fund-raiser,” she says. “They didn’t exist. The money was simply to pay for the costumes, which were extremely elaborate.”

Some elements of cultural life in Taliesin West weren’t quite so demanding. Olgivanna, an adherent of the mystic philosopher G. I. Gurdjieff, would host evening salons to discuss philosophy; on Sunday mornings, Wright would do much the same, opining on whatever ideas were occupying him at the time. Wright was a film buff and hosted regular movie screenings on site. A list of films screened for the fellowship in the late ’30s and early ’40s suggests a man with eclectic tastes that ran high and low: heavy doses of Soviet cinema like Alexander Nevsky, works by French auteurs like René Clair, and plenty of Hollywood fare like Robin Hood, Stagecoach, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. But even with the fluffiest movies, members of the fellowship were expected to be conversant in film and ready for a debate. Montooth recalls one of the Sunday morning chats following a screening of a particularly mediocre crowd-pleaser. “He got so much out of it that we had no idea existed. He brought some real intellectual questions too. It got us to understand that there was more than what you saw on the screen.”

Wright’s reputation rose and fell after the Depression, but by the 1950s, as Taliesin West expanded, it became recognized as a major feat of Wright’s late career. When the architect Philip Johnson visited in 1949 for a commentary in Architectural Review, he declared Wright the “greatest living architect,” thanks in part to Taliesin West. Johnson had been dubious about Wright’s work for years; he reluctantly included Wright in a major 1932 Museum of Modern Art exhibit he’d curated, mainly to satisfy crowds who might otherwise wonder why the world’s most recognizable architect was excluded, grousing that Wright had “nothing to say” about contemporary architecture. But this time he celebrated Taliesin West as a nervy retort to cool, boxy Modernism, proof that Wright was still “inventing new shapes: using circles, hexagons, and triangles to articulate space in new ways.”

Wright fell ill at Taliesin West in April 1959, shortly after Easter, when he took in a vocal performance of the fellowship choir, a Beethoven piano piece, and a screening of a movie about the life of Jesus, Day of Triumph. A bowel obstruction was removed, but Wright died three days after surgery in nearby Scottsdale on April 9. He was 91. Though he was buried in Wisconsin, in 1985, according to Olgivanna’s wishes, his remains were cremated and are now interred at Taliesin West.

In the years until her death in 1985, Olgivanna sustained the fellowship and preserved the culture of salons and performances there, often through performances of her own compositions. Today, students at the architecture school still travel to Spring Green and Taliesin West. But the school has been forced to change in recent years, formally separating from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 2017 to maintain its accreditation. There are remnants of the old fellowship there today: Students still put in kitchen work, but there are no 7:15 a.m. choir practices or full-dress Gilbert and Sullivan productions. Weekly formal dinners have been supplanted by monthly design talks.

Stuart Graff, president of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, sees the facility as looking for new ways to live up to that Lao Tzu quote. “Architecture for him ultimately ladders up into something that we would today call an ecosystem,” he says. “Somehow the buildings make the landscape better. The landscape makes the building better and both make the people better. And the people make both the buildings and the landscape better.”

If that endures, says Casey, it will be thanks to the spirit that kept the fellowship together after the Wrights. “After Frank Lloyd Wright died, a lot of people thought, ‘Well, give it a few years and the whole thing will fold.’ It didn’t, because there was Mrs. Wright, who was a very powerful leader, and she was surrounded by a cadre of longtime people who had worked with Wright,” she says. “And then ’85 comes and Mrs. Wright passes: ‘Well, now the disciples there on the hill, they’ll probably just fade out pretty soon.’ They didn’t, because these core people were driven by a vision to continue the search for a meaningful, rich, creative environment that brings beauty to people’s lives.”